To read the first part of this article, please click here.

The first skit, called "The Coat," featured a protagonist in public housing who had recently come from a recovery program and whose social worker sent her off with medication but little other social support. At the end of the skit, this protagonist, Tanya, collapsed and died from heat stroke. Her neighbors didn't understand why she wore a winter coat on the hottest day of July, but instead of intervening, dismissed her as that "crazy lady."

Then it was time to flip the script: as the group began performing the skit again; as Tanya's social worker discharged her, spec-actors in the audience stopped the scene and had Tanya ask more questions about who would check up on her, and whom she could call for help. The "social worker" had to improvise her responses. She was nice, but honest that Tanya's insurance wouldn't cover home visits after a month. Then she gave Tanya a list of service providers she could call for help. Next, the group and spec-actors improvised a scene of Tanya calling down the list of these providers, looking for help with the side effects of her medicine. While Tanya was able to reach someone on the phone, the conversation that followed was not enough to help her get the help she needed. Andres reflected back to the audience that it is hard for many people to access social support, even if it does exist.

Over the afternoon, each group performed their skit, and then the spect-actors actively changed it. In one scene, about "Kerry," a woman who had begun to hear voices as a result of a traumatic brain injury, a doctor was challenged to treat her with more respect when the spec-actors added a supportive nurse character. In another scene, “Stacey,” a fourteen-year-old girl who was bullied at school and found solace in talking to people she didn’t know over the internet, found new support when the spect-actors added people in various parts of the scene (a concerned teacher, a concerned father), as well as suggesting to Stacey to reach out to her dad about her day at school. These proposed solutions changed the story so that “Stacey” was able to stay away from predators.

In yet another scene, “Sarah,” a woman who struggled with mental illness, was evicted due to a group of neighbors that were very judgmental and not understanding, yet when the spec-actors added a new neighbor, she was able to facilitate communication between “Sarah” and the other characters. In another scene, “Emily,” a foster teenager living with her grandmother and uncle, was able to avoid killing herself in the retake, at least temporarily, because the spect-actors added a classmate able to listen to her and help diffuse the tension by going for a walk.

Every participant had a different comfort level in speaking up to stop a scene and make changes, and in improvising new storylines. But, in the small-group debriefing sessions that followed, all the participants had a chance to say what they had learned through the exercise, and how they thought that, individually and collectively, we can deal with stigma. When all the participants came together again, the conversation centered on how to take what we experienced today and use it in real life. Participants saw that not only professional service providers, but neighbors, friends, and family are crucial in person's mental health. Listening, and offering a supportive word or presence, went a long way in helping our protagonists face oppression. We also saw that making one small change didn't necessarily solve the problem, because the actors and spec-actors didn't idealize human beings or social structures. Stigma, oppression, and discrimination can't be eliminated all at once.

In the past year, the Health Disparities Committee has committed to addressing stigma and discrimination through workshops like this, to build solidarity and relationships across the stigmatizing characteristics and conditions that keep our community divided. Incorporating the spirit of social movements like Occupy Wall Street and Occupy DC, the committee explains how stigma divides members of the 99%, weakening our ability to organize and challenge the 1% for the resources we all need to be healthy and happy.

The day closed with three speakers actively involved in that ongoing battle: Wallace Kirby of the PEERS Coalition, a group of formerly incarcerated activists and their allies who work to change the criminal justice system's treatment of people with mental illness; Gail Avent, founder of Total Family Care Coalition, an advocacy group that helps families in the DC area access community services and resources; and Michelle Beadle-Holder of the MWPHA Health Disparities Committee, who encouraged anyone interested to join the committee and help plan events like this, and in particular to join us for the We Can End AIDS Mobilization on July 24. Each speaker shared some of their personal story that led them to become activists and community organizers. The day closed out with one final improv exercise in which participants were asked to yell out some of the emotions that came up during the workshop: hope, freedom, courage, stress, pain, creativity, frustration, peace, anger, and love. Then five volunteers created a repetitive sound and movement in response to one of the emotions they heard being shouted. They continued this for a few seconds to playback these feelings back to the participants.

As participants said their goodbyes, it was obvious how well the workshop had brought people together. People who had never met hugged and exchanged phone numbers and email addresses, and thanked the facilitators and especially Andres for an amazing experience.

If you want to learn more about this workshop, or are interested in having a workshop created for your organization, feel free to contact Andres at Andres@prometheancommunity.com

Special thanks to Andres Marquez-Lara and Karyn Pomerantz for their edits and contributions to this article.

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Flipping the Script on Stigma: Scenes from the June 23 MWPHA Workshop - Alana Black and Charlotte Malerich

When someone says the word "theater," what comes to your mind? Entertainment? An escape from reality? An unfolding story that, no matter how intriguing it may be, you can only watch?

Though theater played a key role in the MWPHA workshop held on June 23, the event was about as far from a passive, reality-eschewing experience as it could possibly be…though it was entertaining at times!

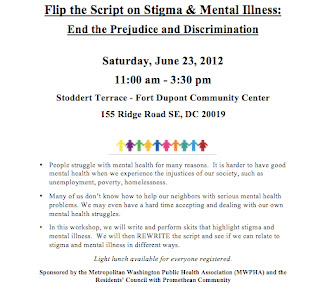

Entitled “Flip the Script on Stigma and Mental Illness: End

the Prejudice and Discrimination,” the workshop was a collaboration between the

MWPHA and two other organizations: Promethean Community, which utilizes theater

techniques to help community members find new ways to relate to each other, and

the Stoddert Terrace–Fort Dupont Residents’ Council, which is composed of representatives

from two public housing complexes in the District and focuses on residents’

rights and collective well-being. The workshop was held at the complexes’

shared community center.

The event opened with a greeting from Kenneth Council,

president of the Residents’ Council, followed by remarks from Andres

Marquez-Lara, founder and president of Promethean Community. Kenneth welcomed

the community members and public health workers alike who had showed up that

morning, and Andres described the rules and the agenda of the workshop, which

were heavily influenced by “theater of the oppressed” (TO).

Originally developed by theater practitioner Augusto Boal

and based on the research of educator Paulo Freire, theater of the oppressed lets

members of a community use theater as a way to promote social action and change.

While there are various techniques within TO, the June 23 workshop was inspired by

forum theater, a technique where a performance that depicts an

oppressive situation is performed in front of an audience, called

“spect-actors”. After the first performance, the scene is performed again, but

this time the scene can be changed by the spect-actors. If they choose not to

change the performance, the scene goes to its natural tragic ending. If they

choose to change it, all they have to do is yell “Stop!” and suggest a new

course of action for the protagonist, or insert a supportive element in the

scene. The spect-actors cannot do away with the oppressive elements, but they

can help the protagonist navigate them. The proposed changes must be realistic.

To get comfortable with each other and to mentally prepare

for the day ahead, participants took part in a series of icebreakers. First, Andres

had everyone pair up and play Rock, Paper, Scissors. Whoever won the best two

out of three in each pair went on to challenge the winner of another pair, as

would be expected. However, in a twist, the loser of each pair was to become

“the biggest fan of the winner,” and they would follow the winner of their

individual pair as his or her cheerleader. By the end of the icebreaker, there

were only two competitors and a room full of fans divided evenly among the two.

After the final victor was declared, everyone was united in cheering for the

one winner; her success was shared by everyone.

Other icebreakers were more directly involved with stigma

and mental illness. Andres had workshop participants line up along an imaginary

spectrum gauging their comfort with public speaking, talking about mental

illness, and willingness and confidence to interject when they observe

discrimination and prejudice. Everyone placed themselves on different points of

the spectrum depending on the question; no one was equally comfortable or

uncomfortable with every situation mentioned. This allowed participants to see

their relationship to others in the criteria that was being used.

The last icebreaker was especially introspective.

Participants were encouraged to walk around the room in silence at whatever

pace and in whatever direction appealed to them, and to think about how they

thought about others in the room. They were then asked to consider the labels

they assign to themselves, how they feel about those labels, which labels they

want to keep, and which ones they want to cast away; to think of the labels

they placed on the other participants in the room, and be mindful of their

response to the labels they observed in others. Afterwards, everyone broke into

threes to talk about thoughts that came to mind, sharing as much or as little

as they were willing to.

Then, it was finally time to get to the scenes. Workshop

participants were split into smaller groups based on birth month. Each group

had one or two volunteer facilitators, who had met beforehand with Andres in

three previous training sessions. The facilitators got the small groups

comfortable with one another through an introduction warm-up, then each group

got started coming up with a situation and characters for their five-minute skit,

which would depict someone with a mental illness who encounters a problem

because of stigma or prejudice. Once the group had a story and characters, they

rehearsed until they felt it was ready to be performed in public.

Lunch time: over sandwiches and snacks, participants had

time to relax and get to know each other better. After lunch, the room was reconfigured

into an audience and floor space for the stage, and Andres asked which group

wanted to perform first. Hands in the audience shot up eagerly.

Check back tomorrow evening to find out how the remainder of the workshop went!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)